Daitokuji 大徳寺 ‘Temple of Great Virtue’

Described by the writer Jon Carter Covell as ‘the most important Zen temple in Japan’, the distinguished temple complex of Daitokuji in Northern Kyoto has often been at the centre of Japan’s cultural, artistic, religious and political history.

However, for the first almost two centuries of its existence, it struggled for its survival. Established in the early 14th Century by the esteemed Zen master Myōchō Shūhō (Daito Kokushi, 1282-1338), it survived decades of relative financial austerity and political instability to eventually recover and find prosperity from the late 15th Century. Acquiring fame also as a centre for tea ceremony, Daitokuji retains its reputation today for its architecture, meticulous gardens and precious collection of artistic and cultural treasures.

Daitokuji today is one of 15 headquarters of the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism. Although far surpassed in institutional terms by its main Kyoto rival, Myoshinji, it still has a considerable nationwide organisation of two active monasteries, 200 branch temples, and over 50,000 adherents. It possesses 24 subtemples and an additional 44 subsidiary buildings across its 57 acres of land in Northern Kyoto, an area formerly known as the Murasakino (‘Purple Fields’).

People

Myocho Shuho (1282-1338) –

Better known by his honorific name, Daitō Kokushi (‘National Teacher Daitō’). As an up-and-coming Zen master untainted by links to the authoritarian Hōjō clan in Kamakura, Daito managed to gather enough support and patronage for the construction of a new temple in Northeast Kyoto, what would become Daitokuji, and would serve as its first abbot.

Praised in typical fashion by the famous 18th Century Zen master Hakuin Ekaku as “Japan’s most poisonous flower”, Daito gained fame for allegedly spending twenty years living under the Gojo bridge in Kyoto among beggars as part of his spiritual training. A famous story has it that an emperor, seeking him out among the beggars and aware of his fondness for a type of melon, handed each beggar a melon to see in their eyes who was most excited. With Daitō having revealed himself, as a philosophical test the emperor told him to receive the melon without using his hands, to which Daitō responded, “give it to me without using yours”.

Daito can be regarded as a historical figure who attempted to balance the rigorous, individualistic life of a Zen disciple with the demands of being the founder of an institution. In the period between his move to Murasakino in 1319 and his death in 1337, he only travelled on two occasions, preferring to stay in Daitokuji and concentrate on his work there. Such permanent residence was quite unusual for a prominent Zen master, but he seemed to take virtue from it. After his trip to Kyushu he composed the poem:

“No footprints of mine are seen

wherever I wander;

on a tip of a hair I left the capital

on three drum taps I am leaving Kyushu”

Most, if not all, of today’s Rinzai monks consider themselves Daitō’s spiritual descendants. Monks today still come to Daitokuji to train according to his strict rules, and his ‘Final Admonitions’ are chanted daily in monasteries across the country. Furthermore, as a native Japanese trained in Japan as opposed to China, he was one of the pioneers of a period in which Zen was becoming more distinctly Japanese. Daitokuji was indeed significant for being the first major monastery in Japan founded by a native Japanese who had never travelled to China.

Tetto Giko (1295-1369)

Daito’s appointed successor as abbot of Daitokuji, Tetto Giko was an able administrator and abbot for 31 years. He stabilised Daitokuji’s sources of patronage during the precarious political situation of the 14th century, and managed to add a Buddha hall and the first sub-temple, Tokuzenji to Daitokuji’s architecture. Like Daito, Tetto was known for being an often strict and intense teacher, once threatening to cut off his own tongue if someone did not experience kenshou (‘initial awakening’) during a 90 day training session. Fortunately, a pupil, Gongai Sochu (1315-1390) did manage to achieve this, and indeed Gongai became Tetto’s primary successor at Daitokuji.

Fortunately for historians, Tetto was also a meticulous record collector. In 1368 he evaluated the size of Daitokuji as having around 200 monks, confirming that it remained relatively small several decades after its founding.

Ikkyū Sōjun (1394-1481)

The famous Ikkyū was an eccentric calligrapher, poet, and often vagabond known in popular culture (through an animated children’s TV series) as a mischievous hero. His connection with Daitokuji began in earnest when he saved Daitō’s calligraphy from fire during the Ōnin war (1467-1477). Subsequently, in 1474 he was designated abbot, a role which, given his bizarre character, he was perhaps reluctant to take on.

Plenty has already been written about Ikkyū. Suffice to say he lived at a time coinciding with Daitokuji beginning to find some fortune and prosperity. Ikkyū himself brought links with rich merchants in Sakai, associations with poets, the tea ceremony and the imperial family, and guided Daitokuji on the path to becoming an artistic and cultural hub.

Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591)

An even more famous name to be linked to Daitokuji, Sen no Rikyu is globally renowned as the master of chanoyu tea ceremony. Rikyu underwent Zen training at Daitokuji and his grave can be visited at the sub-temple Jukoin, where a ceremony is held by tea ceremony schools every month.

Daitokuji retains strong associations with Rikyu as the setting for the drama which led to his death. Rikyu reconstructed the impressive, vermilion Sanmon (main gate) in 1589 and placed a statue of himself inside on the second storey. His master, the volatile shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598), was furious at the implication that he may have to walk beneath a statue of his tea master to enter the temple. It has been supposed that this was the reason Hideyoshi ordered Rikyu to commit ritual suicide in 1591. The statue itself was ceremonially ‘crucified’.

OTHERS:

Takuan Soho (1573-1645) – made 154th abbot of Daitokuji in 1608, Takuan was one of the most famous Zen masters of his time. He was prolific in his writing and artistic endeavours, and many people interested in Zen today come to know him through his work, The Unfettered Mind. He was particularly known for drawing on the art of swordsmanship and fusing it with Zen ritual.

Kobori Enshū (1579-1647) – a famous aristocrat and tea master associated with the temple, who designed the Bosen-seki teahouse in Daitokuji’s sub-temple Koho-an. His style of tea ceremony has been labelled ‘Enshū-ryū’.

Kogetsu Sogan (1574-1643)

Son of Daitokuji’s abbot Tsuda Sogyu, Kogetsu became a leading Daitokuji monk, tea master and colleague of Kobori Enshu. Kogetsu’s achievements are an example of how Daitokuji cultivated the arts in the Zen Buddhist world. Best known as a peerless connoisseur of calligraphy, he left behind ‘Bokuseki no utsushi’ (Copies of Ink Traces), a record of calligraphy produced by Zen monks from 1611-43. A chronicle in the Chinese genre of ‘things seen and heard’, his work is frank about commercial interests in the early 17th century art world in Kyoto. It reveals disputes over the authenticity of works and the high value placed on Bokuseki calligraphy as an object for the tea ceremony.

Timeline of significant events

1319 Zen master Daito moves to the Murasakino area of Northern Kyoto, merely a sparsely populated area of rice paddies, forests and wild marshes.

1325-26 Dharma hall (hatto) constructed, marking the beginnings of Daitokuji as a temple. According to Chinese Sung Dynasty precedent, all monks used to assemble there every morning and night to listen to Daito’s speech and the subsequent question and answer between monks and Daito.

1326 A solemn inauguration ceremony for the Dharma hall and the temple as a whole. This was a public demonstration of the sources of sponsorship and support Daito had managed to gather to build Daitokuji.

According to sources, there was a solemn procession from the gate to the new Dharma hall, led by Daito who was wearing bright red Chinese slippers curled upwards. Traditionally the abbot then engages in an impromptu ‘Dharma combat’ question and answer session with the congregation. On this occasion, though, it was ceremonial and much deference was shown towards Daito. Overall, the ceremony was quite conventional in taste, following standard Chinese Buddhist formulae such as the line in Daito’s speech ‘I pray that the emperor will live for tens of thousands of years’. Most likely, this was because the two emperors present were his most powerful patrons.

1333 Emperor Go-Daigo confirms the Kyoto precincts of Daitokuji consisting of a generous twelve acres (today Daitokuji has more than 57 acres), but with only two main buildings, the hatto and the recently donated abbot’s residence. Daito forbade the building of a separate memorial hall for himself after his death. Instead, he was remembered with just a memorial alcove within the abbot’s residence, the Unmon-an, which can be visited today. Daitokuji was still a relatively humble temple at this stage.

14th – mid-15th Century

After its initial founding, Daitokuji endures a century of relative austerity. In its first decades, Daitokuji was subject to the turbulent political transition from the Kamakura to Muromachi periods, and was at various times elevated or ignored in the all-important ‘Gozan’ ranking system of Zen temples. Its status changed according to the political will of the main political actors, including the two emperors, the reigning Go-Daigo and the former emperor Hanazono. Indeed, Daitokuji’s patronage was split between these two powerful figures. Daitokuji’s lands were also vulnerable to confiscation by the Ashikaga shoguns and partisans, particularly after the defeat of emperor Go-Daigo with whom the temple was associated.

1426

The Daitokuji monk Shunsaku Zenko compiles the first biography of Daito. Daito has always retained his status as a revered Zen master. In fact, on the 22nd day of each month, the current abbots of all 24 sub-temples assemble for a memorial service in honour of Daito and place flowers, green tea and other offerings before a life-size wooden effigy of him. In November every year, this ceremony is performed publicly in the Dharma hall. A representative of imperial family is invited, along with prominent tea masters, dozens of abbots from other temples and all the monks of Daitokuji and Myoshinji. Every 50 years there is an even larger ceremony, which in May 1983 attracted 3000 guests. Emperor Showa himself sent a personal donation, in honour of the links between the temple and the imperial family.

Mid-16th century Most of Daitokuji’s architecture is destroyed by fire.

1582

Oda Nobunaga’s funeral held at Daitokuji, overseen by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Hideyoshi then built Nobunaga a mortuary sub-temple, Soken-in. Daitokuji was lavishly patronised by Hideyoshi, who regularly participated in tea ceremonies there.

1629

Daitokuji plays a prominent role during the Purple Robe Incident. Many Daitokuji abbots become rare symbols of political protest.

1635 Abbot’s quarters (hojo) completed.

1661-1673

(Kanbun era) Daitokuji reaches the peak of its prosperity. The main temple and its 24 sub-temples were architecturally distinguished with gates, halls and meticulous gardens. The temple had by now accumulated many profoundly important paintings, ceramics, tea utensils, altar figures, screens and calligraphic scrolls. Its Zen gardens are pinnacles of the genre, and its tea rooms are considered the centre for chanoyu tea ceremony.

Modern era – Daitokuji’s impact on the Western understanding of Zen Buddhism

1950s and 60s – Daitokuji opens itself to American students coming to study Zen, eventually having an influence on the American arts and culture of that generation. Those who came to train in Zen and reside at Daitokuji include the Beat-associated poet Gary Snyder and the poet-filmmaker Ruth Stephan.

1958 Ruth Fuller Sasaki renovates the subtemple Ryosen’an and converts it to house the first Zen Institute of America in Japan.

1970s and 80s – Abbot Kobori Nanrei Sohaku, a disciple of Daisetsu Suzuki, mentors many American students and holds zazen sessions in the Ryokoin. Among his students is James H. Austin, neurologist and author of Zen and the Brain.

Features

As mentioned, Daitokuji is famous for the treasures in its collections. Indeed, it has one of the most important monastic treasuries in the country. The temple has held kaichou or mushiboshi since the Edo period. These are regular viewings of the temple’s treasures, open to the public. Originally held in the seventh lunar month to expose treasures and paintings to air and sunlight, slowing mould and insect damage, by the 18th Century these had become carnival-like events.

There are many treasures to be found among its grounds and subtemples. The Jukoin subtemple, famous for the grave of Sen no Rikyu, also houses works by the eminent Kano-school master Kano Eitoku (1543-1590). Elsewhere, there are sliding door paintings and scrolls by the most famous Edo-period Kano academy artist, Kano Tan’yu. Daitokuji is also well-known for possessing rare 13th century hanging scrolls by the Chinese master Muqi (National Treasures). Equally unusual is a Go (Chinese board game) board once used by both Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the eventual unifier of the country, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Regarding the architecture, one of the highlights is the Sanmon main gate, the southern end of the temple’s overall north-south axis. However, more than simply an attraction for the tourist, this gate, with its eventful history, can help us reflect on our interpretations of Daitokuji. Looking at the temple from a more holistic approach and challenging existing art historical discourse surrounding the temple, historian Gregory Levine discusses the gate in the context of how Daitokuji has been perceived, particularly in Western scholarship. The main features of the gate are typical of a ‘zen-style’, consisting of slender pillars, clustered brackets, and ornamentally carved components. Usually Daitokuji is seen in this way: through a rhetoric of cultural particularism as an archetypal ‘Zen’ temple.

However, as this gate shows, Daitokuji was also designed to accommodate mainstream Buddhism, and fulfilled the needs of any large temple community. The Sanmon gate was a venue for transmission rites, and this is shown in particular by a sculptural ensemble on second floor. This ensemble consists of Sixteen Rakan sculptures, and paintings of dragons, celestial beings and guardians by the eminent painter Hasegawa Tohaku. Breaking away from any characterisation of Zen temples as timeless, transcendental spaces, Levine emphasises the gate as a venue for rites and rituals, the site of communal identity, and a ‘gate of memory’.

As a centre for tea ceremony and particular object of attention for Westerners, from Ernest Fenellosa to Beat poets, perhaps Daitokuji is particularly susceptible to romanticisation at the expense of understanding it with a more diachronic, critical eye. It is important to bear in mind and question the filters we may impose upon our experience of Daitokuji due in large part to the 20th Century interpretation of Zen Buddhism.

A short piece is not sufficient to comprehensively describe Daitokuji. This is not only due to its number of treasures, or links with central characters and events in Japanese history. More importantly, it is also because it is a temple which has changed radically in character over the centuries since its humble beginnings, and which has come to embody various meanings and reflect various interpretations, a certain Western romanticisation merely being one of them.

References

Addiss, Stephen, The Art of Zen, (New York, 1989). For an examination of calligraphy and art created by Daitokuji-affiliated artists.

Kraft, Kenneth, Eloquent Zen, (Honolulu, 1992).

Levine, Gregory P. A., Daitokuji: The Visual Cultures of a Zen Monastery, (Seattle, 2005).

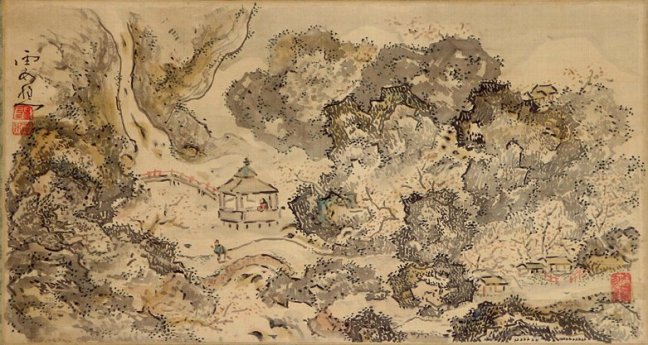

Nagasawa Rosetsu famously pranked his eminent master, the painter Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795), by giving him a painting to critique, listening to the scathing judgement, before revealing that it was in fact his master’s own, leading to his expulsion from the studio. In contrast to this ostentatious behaviour, Ito Jakuchu embodied an ‘eremitic eccentrism’, derived from the story that he had received no formal training (a myth), his sudden appearance on the art scene, and his very reclusive, monastic lifestyle.

Nagasawa Rosetsu famously pranked his eminent master, the painter Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795), by giving him a painting to critique, listening to the scathing judgement, before revealing that it was in fact his master’s own, leading to his expulsion from the studio. In contrast to this ostentatious behaviour, Ito Jakuchu embodied an ‘eremitic eccentrism’, derived from the story that he had received no formal training (a myth), his sudden appearance on the art scene, and his very reclusive, monastic lifestyle.

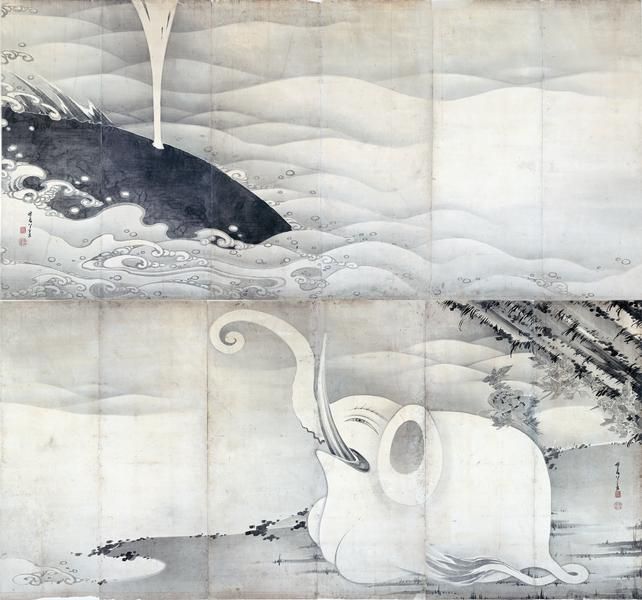

Most striking of all to modern eyes, perhaps, is White Elephant and Other Beasts, in which Jakuchu divided the paper surface into six thousand small squares as if it were an experiment in modern expressionism.

Most striking of all to modern eyes, perhaps, is White Elephant and Other Beasts, in which Jakuchu divided the paper surface into six thousand small squares as if it were an experiment in modern expressionism.